Isla Espíritu Santo: A Living Laboratory in the Gulf of California

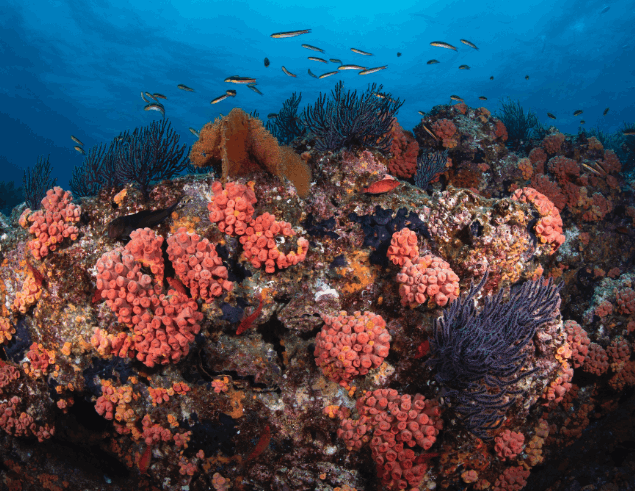

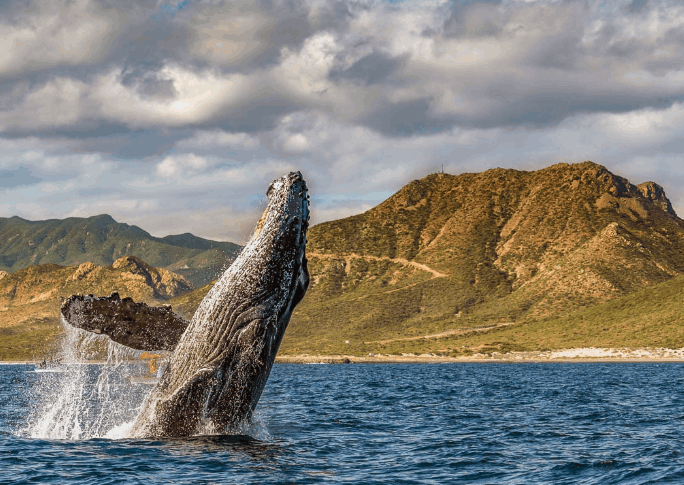

Off the sun-drenched coast of La Paz, Baja California Sur, lies Isla Espíritu Santo — an uninhabited island of stark beauty, rugged terrain, and extraordinary biodiversity. Designated a protected area and part of the Islas del Golfo de California Flora and Fauna Protection Area, it has become far more than just a postcard-perfect backdrop for ecotourism. It is a living laboratory for scientists from Mexico and around the world.

Follow Us